The idea of the one disenchanted and one enchanted eye haunts me, especially in the expansive territories of the American West. A thriving desert town always conjures up two simultaneous, parallel visions. Through one eye, the prosperous homes, businesses, and lights; through the other, the same site after a century of abandonment: toppling walls, shreds of faded fabric, piles of rust and sand.

These paintings, drawings, and sculptures represent my first attempt to communicate a persistent and haunted double-vision. I hope that they will make the viewer look twice—and sometimes, twice at the same time.

The small sculptures that serve as references for the painting Slow Growth are made largely of lint—material harvested during a Lint Cleaning and Restoration Camp at Great Basin NP’s Lehman Caves. As one eye helped me collect the hair, clothing fibres, and skin cells from speleothems, the other resurrected the tens of thousands of visitors from all over the world who had left these small pieces of themselves behind.

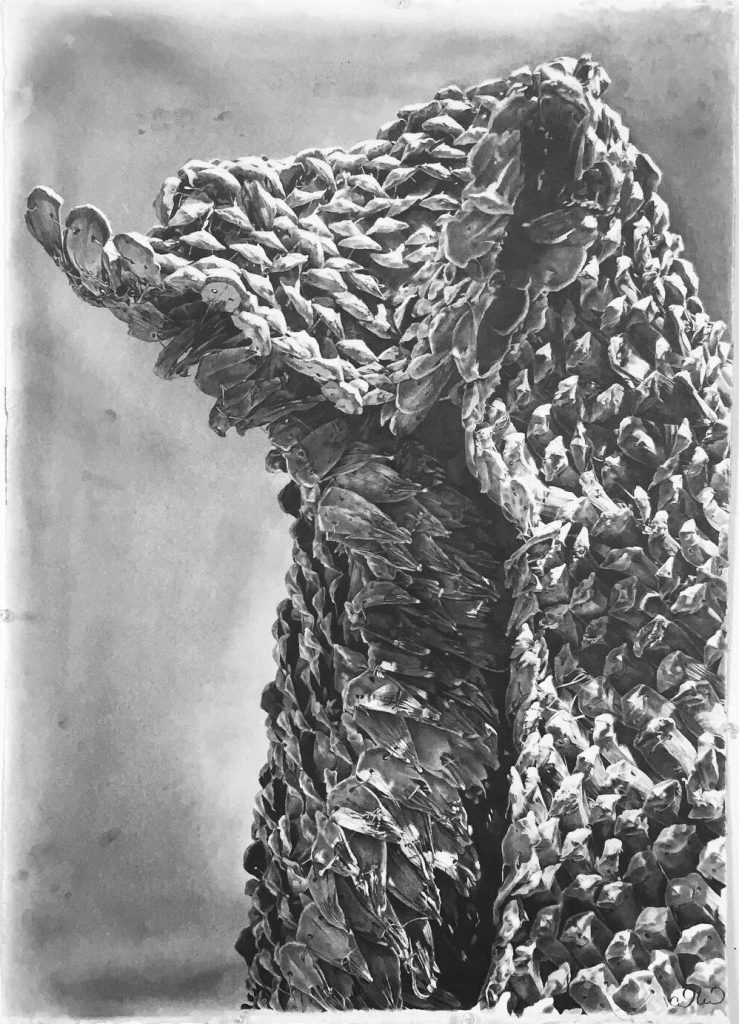

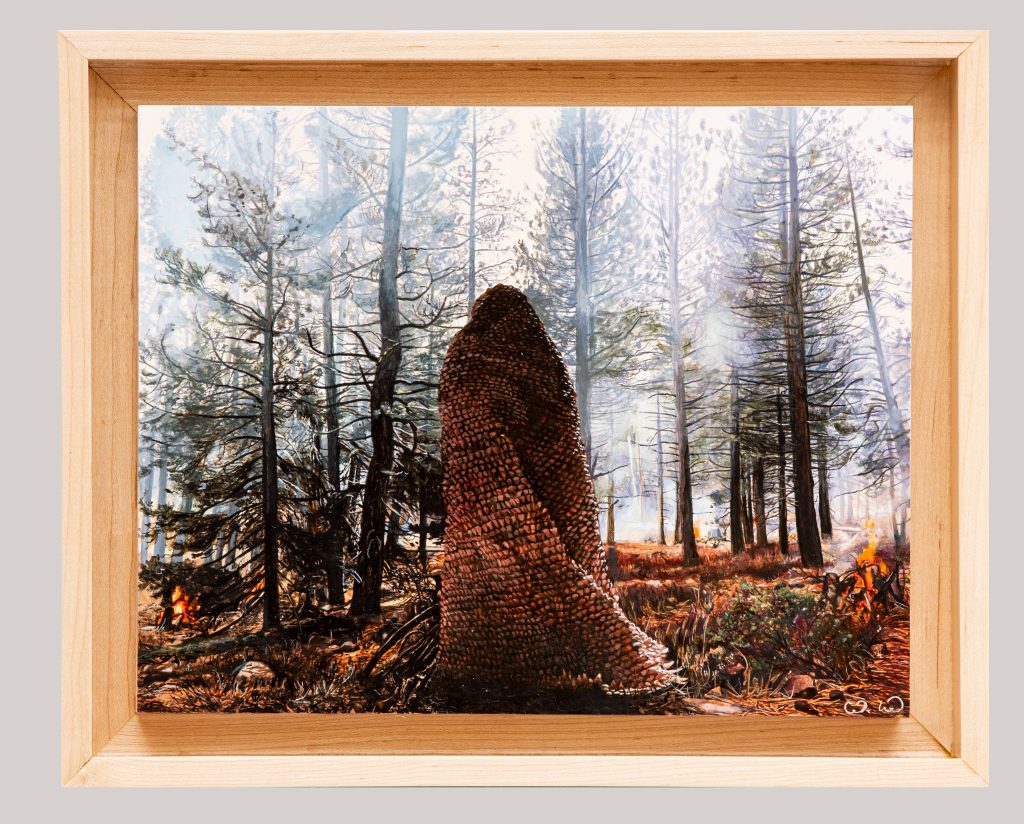

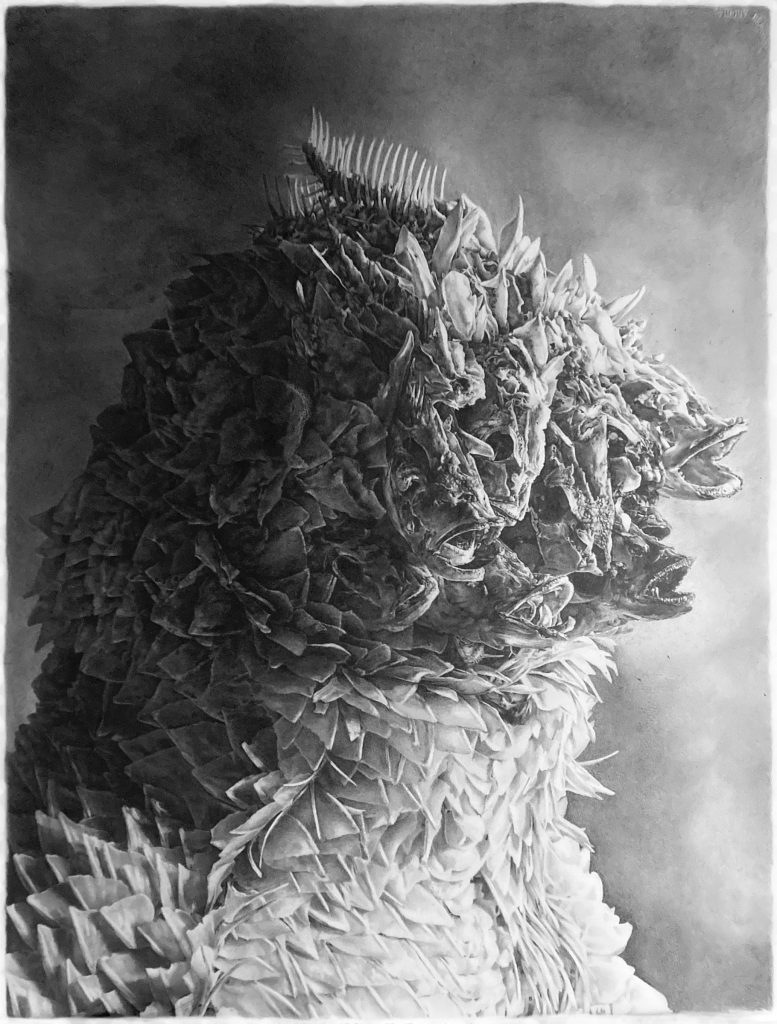

The heavily timbered and replanted forests of the eastern Sierra Nevada are slowly regaining a sense of wilderness, which I tried to embody in Pine Cone Shroud and its companion pieces.

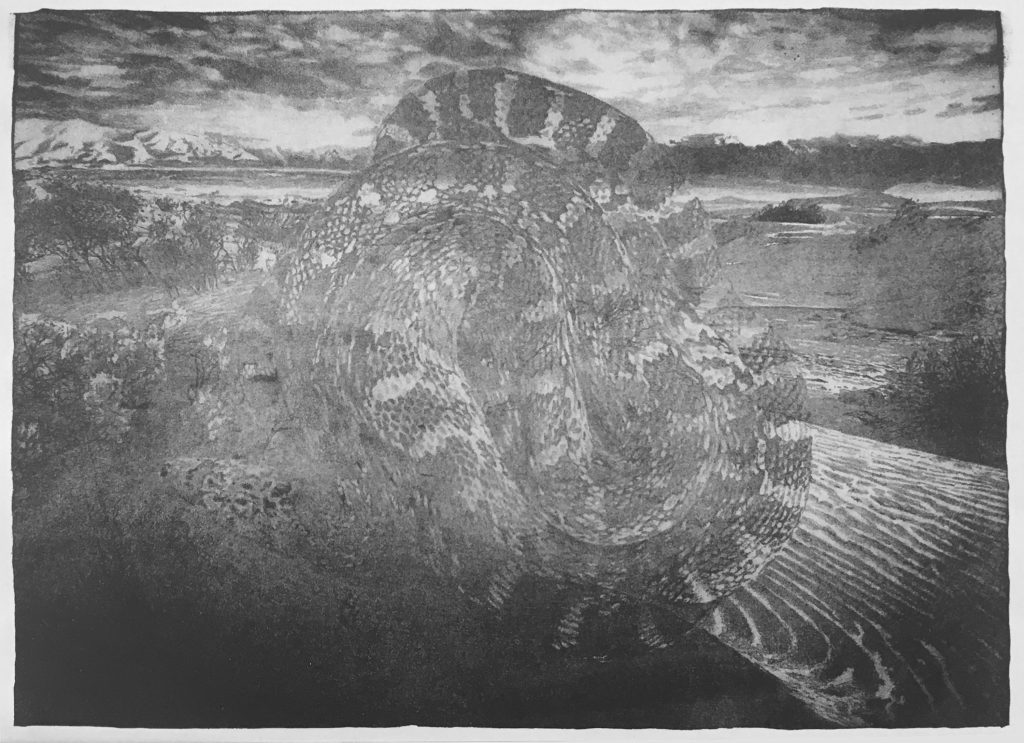

The Salton Sea, most recently filled through a 1905 engineering mishap, demands to be seen with its history and future superimposed. You hold in your mind the fact that native Torres-Martinez communities were catastrophically flooded here, reducing the tribe’s lands by half—and the brief memory of the American Riviera, flitting with the ghosts of frolicking beachgoers—and the ankle-deep piles of barnacles and tilapia bones that comprise the current, ominously retreating shoreline—and the wind-whipped pesticide storms that may one day rise out of the evaporated lakebed.

An ineffably beautiful building designed by Richard K. A. Kletting, taken down by fires and winds nearly a century ago, leaves its phantom hanging in the air in Afterimage of Saltair I (Great Salt Lake).